Chip scandal hurts high-tech push

Chen Jin became a national high-tech hero almost overnight, but his easily-won fame fades quickly as his "breakthrough invention" -- computer chips -- was proven to be a fraud.

|

|

The achievement was then hailed as a milestone for China's rising technology industry. Chen was named one of the country's brightest young scientists. He received a huge research grant from Beijing, headed his own research institute and was named a dean at one of China's most prestigious universities.

But on Friday, Jiaotong University, where Chen and his team were based, announced that Chen faked his research. He was fired from Jiaotong and stripped of his state honors and privileges. University officials called his actions "despicable" and Beijing said he would never again be allowed to do government research.

The disclosure has turned into an embarrassment for Chen, Jiaotong University and the country, which has been trying to lure talented scientists back from overseas in the hopes of creating its own prestigious research and technology centers, according to a New York Times report.

No longer content with being the world's low-cost factory floor, China desperately wants to move up the economic ladder and to show it can compete as a scientific and technological power.

The country sent its first men into space three years ago; it is building its own high-tech parks and 3G mobile technology. Internet companies are taking off here.

In addition, Shanghai has been moving aggressively to develop into a major center for microelectronic chips.

Few people symbolized the rise of China's scientific elite like Chen, a charismatic young scientist who worked for a multinational corporation and then returned home.

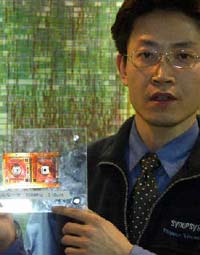

When he announced the results of his research at a series of press conferences in 2003 and 2004, he smiled for the cameras and held up a glass-like plate bearing a new family of Chinese born computer chips, dubbed "the Hanxin," or China chip. Newspapers here called it a "breakthrough" that could help end foreign dominance of the chip industry.

Then, last December, a former colleague - and, by some accounts, a group of lab assistants - sent a letter or a series of letters to the government. They said Chen's chips were fake. One of the so-called whistleblowers even posted the allegations on the Internet. A few weeks later, the government and Jiaotong University announced an the start of an investigation, which ended with his dismissal Friday.

If Chen's team did indeed create a fake chip, how they tricked a nation - and a large group of scientific experts from the government and industry - is still unknown. Whether Chen or members of his research team face criminal charges is also unclear.

Reached Sunday by telephone, Chen declined to comment. He simply said: "This is not the right moment to talk," the New York Times reported.

People who know Chen, however, are perplexed.

"He was really brilliant," says Yang Yunxia, a Microsoft employee here. "None of us can understand this."

According to former colleagues, press accounts and his own writings, Chen was born in coastal Fujian Province in 1968, along with a twin brother. He earned a bachelor's degree at Tongji University in Shanghai and then, in 1991, moved to the United States to study computer engineering at the University of Texas at Austin. In 1998, he earned a master's degree and Ph.D. at Texas while working at Motorola's Austin research center, he wrote in his dissertation.

While in Texas, he impressed a lot of people. He co-authored several scientific papers at the University of Texas with Jacob Abraham, a professor of computer engineering and his dissertation supervisor.

"He was a good student," Abraham said by telephone. "His PhD research involved some innovative ideas for testing analog circuits."

Once back home, Chen worked for a time at Motorola's Suzhou research center, not far from Shanghai, before taking a job at Jiaotong University, one of China's most prestigious universities. By then, creating a homegrown digital signal processor chip - a sophisticated microchip that can process digitized data for mobile phones, digital cameras and other electronic devices - had become a priority of the government.

No Chinese company had been very successful. Yet the government, some industry officials say, was pressing Chinese scientists to create such a chip fast. Chen did. Within two years, he announced his breakthrough: a digital signal processor that could process 200 million instructions per second.

This was something big for China. His invention hit the headlines of all major national newspapers in February 2003, like "Homegrown Digital Chip Developed," "China Makes Breakthrough in Chip Development," and "Shanghai Chips Away at High- Tech Industry."

Some stories said China was spending billions of dollars buying foreign made chips to put in electronics equipment. Now, they suggested, China could use its own chip.

That was a banner year for Chen. He was named founding dean of the microelectronics school at Jiaotong. He headed a university research center. He was heavily financed by the government. He was named a Chang Jiang Scholar by Beijing, one of the most prestigious positions for a young scientist.

Chen had overseen a lab of more than 100 researchers. He was highly regarded in his field and also busy creating his own family of companies.

According to press reports, he formed several companies to help design chips, including one based in Texas, which was founded with the help of a former Texas classmate. Everyone in China seemed to be backing him.

When he announced creation of Hanxin II and III in 2004, Beijing's Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the National Reform and Development Commission and the Shanghai government were helping finance his operations.

At that time, the company he formed reported having orders for 3.5 million chips, with possible deals from major companies like IBM. Two years later, according to press accounts, the whistleblowers came forward. Some colleagues had a dispute with Chen and they began contacting the government. They claimed, according to the media, that migrant workers had simply scratched away the name "Motorola" from a chip and replaced it with "Hanxin." They gave details of an array of companies that Chen operated to profit from the big government contracts he received.

Indeed, there were lengthy press reports about the fake chip scandal well before the government investigation was completed this year. On Friday, however, the official Xinhua news agency reported that government had concluded Chen had faked the computer chips findings.

Jiaotong University issued its own press release Friday, saying Chen had breached the university's trust and exaggerated his findings.

The school also said, "None of the Hanxin chips can be ranked as world leading DSP chips."

The government in Beijing canceled the Hanxin project and recalled all of its scientific funds.

The case is also a serious blow to the enormous ambitions of Shanghai, which is fast developing into a microelectronics and semiconductor design and manufacturing center.

On the Jiaotong campus, several students expressed dismay at the scandal Sunday, worrying about how it might affect their careers, but also wondering whether Chen was unfairly singled out.

"Professor Chen is really unlucky," said a student named Wu. "He lied and was caught. I think there are other people faking their research but they haven't been caught yet. He's probably not the worst."

Another student, named Wang, who asked not to be completely identified, added: "I'm not surprised by the scandal. Now a lot of professors are like businessmen. They are good at talking and promotion and many of them have their own companies and make as much money as they can."

News&Opinion

more

more- 2009 World Stamp Exhibition opens in central Chi...

- Saltire Scholarships encourage more Chinese to s...

- S Korea condemns Japan over approving distorted ...

- China Southern Airlines resumes flights to Tibet

- Chinese students write new "Journey to the West"

- Mexican university, city gov't offer grants for ...

- Internet worsens Chinese youth's language skills

- Learning Tibetan language no longer a privilege ...

Policy&Laws

Chinese farmers in need of more books, films

BEIJING, April 7 -- Rural households in China spent an average o...

China to promote book reading among children, yo...

BEIJING, April 6 (Xinhua) -- China plans to launch a se...

China Education:Hong Kong education expands coll...

HONG KONG, April 6 (Xinhua) -- The Hong Kong Institute of Educati...

print

print  email

email  Favorite

Favorite  Transtlate

Transtlate